General "Mule" Waveren

GENERAL WAYVERNE AND HIS MULE

(From an article in the Daily Oklahoman Sunday Feb. 18, 1940)

General Wayverne is something of an institution in Coal county now. He has been in and around there since 1905. When he was a younger man they say he was as good a hand with an ax or saw as any one in the timber country. For years he made a living sawing wood and doing odd jobs around the farm. And all this with one arm.

General Mule's cabin was saved from certain deterioration by W.M. "Mouse" Basket who had the foresight to preserve it by putting a new roof on it, moving it to a safe location and blocking it high off the ground nearly 30 years ago. Winston Rice has plans of bringing the historic building to Clarita for complete restoration.

Just when General Waveren first met Custer isn't in the records. Probably it was the summer of 1874 when Custer headed a military guard sent with a party of scientists making explorations in the Black Hills of North Dakota. Wayverne's skill as a plainsman and his knowledge of Indians stood him in good stead when, a few years earlier, he joined the army as a scout.

He cottoned to Custer immediately, and was with the General constantly. He says Custer took a liking to him, too, and reposed implicit faith in him. It was from Custer, he says, he got the designation of "United States Scout No. 1, Company M, Seventh Calvary."

Most school boys know the story of the Custer massacre. The Indians were getting out of hand and numerous tribes were uniting against the whites. In the spring of 1876 General Sheridan, commandant at Fort Riley, Kansas., made ready for a decisive blow against them. Three columns under Crook, Terry and Gibbon were sent to crush Chief Sitting Bull, who was somewhere on the Yellowstone river.

Custer and Waveren were under Terry's command, Custer heading a Calvary regiment of 600 men. Terry sent Custer and his command on ahead to bar the escape of the Indians to the east, with orders to wait for the main body of troops under Terry and Gibbon. The rendezvous was to be the junction of the Little Horn and Big Horn rivers on June 26.

At any rate, Custer assumed the band was composed of only 1,200 or 1,500 Pawnee he knew were marching to join Sitting Bull. That was a fatal assumption.

On the morning of the twenty-sixth Custer kept 260 men for a direct attack on the Indians. He assigned about 200 to Major Reno to assault the left flank and Wayverne was sent along with Reno as a scout and guide. That is why he's alive today.

Custer rode for the heart of the line and was quickly engulfed in a hoard of howling savages that outnumbered his command 20 to 1. The massacre was complete, not a man surviving. Major Reno and Wayverne, meanwhile, had carried out their attack on the flank but were repulsed with heavy loss.

They fell back across a creek and held the pursuing Indians at bay until darkness. Next day they had another battle on their hands, and it was in this that General Wayverne lost his left hand. A big Cheyenne stuck a rifle in his chest, but before he could fire Wayverne slapped it away with his right hand. The shot caught him just above the left wrist and practically tore his hand off. He kept going with the others, though, until Terry arrived with the main body of troops a few hours later and rescued the harassed survivors.

General Wayverne drifted around after that. He continued in the army as a scout for a time but by the turn of the century the army wasn't needing old time Indian scouts any more and he was dropped. He worked down through Texas, settled in Hunt county awhile and in 1905 came up to Oklahoma with an acquaintance he had made.

He just happened to land in what later was to become Coal county, and that has been headquarters, more or less, ever since.

A man who had been around as much as the General doesn't stay put indefinitely. He had acquired a mule, and between 1910 and 1915 he covered many a mile with the mule as the only source of locomotion. In the spring of 1915 he went from Coalgate to the Pacific ocean taking three months for the trip to Seattle. He camped out all the time, rode the mule when he felt like it and got back in the autumn and has puttered around ever since. Most of the time he worked for J.C. Collins, a successful farmer and land owner of the Clarita community. Collins took a fancy to the General and sees to it he doesn't lack for necessities now that he isn't as spry as he once was.

Fed McMillan, another Coal county friend, and Earl Mitcham, Coalgate banker, look in now and then to make sure the old scout is comfortable. Not so long ago McMillan gave him a couple of acres and a cabin in a beautiful pecan grove three miles southeast of Clarita, and there the General is living out his span. He keeps the grove and his little two-room home spotless. No weeds or rubbish litter the ground. Stove wood is stacked neatly; rocks and small lengths of petrified wood he has picked up here and there border sandy walks in straight military lines.

Once or twice a week he cuts across the fields to the Collins farm a couple of miles away and once a month he shuffles into Clarita for supplies and to pick up the old age pension check he gets from the State.

But about that mule. Having lived around livestock all his life the general was more than ordinarily fond of horses and such. He acquired this last mule in 1921 and for seven years the two were inseparable. Most of the time they were working on the Collins farm, and when the mule died November 10, 1928, the General felt the loss keenly.

"Well, why don't you bury him out there in the field and sort of take care of the ground?" Collins inquired. The General thought it was a good idea. They dug a hole and buried the carcass and the General went to work. He planted trees, built some small concrete retaining walls and put up a crude concrete head stone. Curiously enough there is no inscription on it because the mule never had a name. Names, apparently, don't mean much to the General. He just called his animal "the mule", and sees no reason for an epitaph.

Now he has built a strong wire fence around the plot, and has marked out his own grave at the foot of the mound where the mule is buried. He thinks it will be a better spot than anything he'd have had if he had gone down with Custer. H.F.J.

Editor's note: Many people in the Clarita area still remember seeing General Wayvern on his walks to Clarita

Joe Ward remembers that Wayverne's first home in this area was on the Ward land, presently owned by the Lee Morrison family. He says the family sold him a small plot of land The General built a small house and a very nice barn to house his mule and when the mule died he buried it on the place. He went to the Dunn ranch nearby and searched their stock until he found another as near like the first as possible and this is the mule he buried on the Collins farm. He would follow the wheat harvest north every summer, leading his mule almost to the Canadian border but never riding him.

He died several years after this article was printed and is buried beside his mule on the plot he so tenderly cared for.

From Denis Rodgers: “When we first knew General he lived on the Ward place near where the first Olney school was. He lived up on Elm Creek. He lived in an old house on the Ward place but he built a new barn, much better than the house, for the mule.

He would walk and lead that mule to town and back and he would go to Kansas and Nebraska working in the wheat harvest and lead that mule all the way, he never rode or worked it. They say he could do as much work in the harvest as a man with two arms.

His first mule died and he bought another as near to resemble the others as he could. He bought it from the Dunn Ranch.

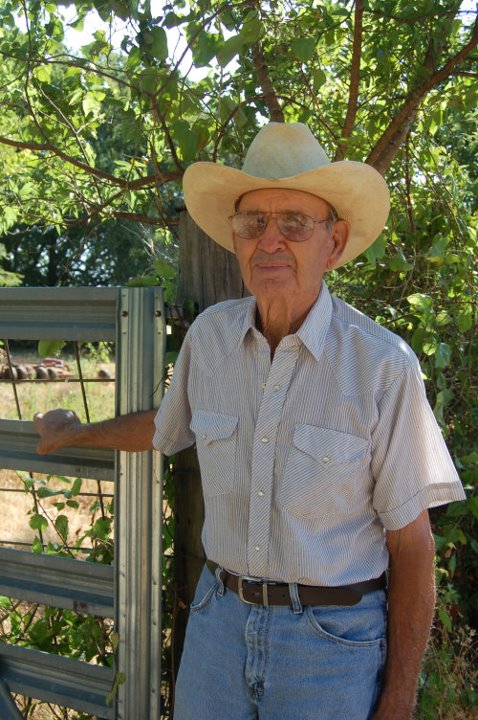

These are the only two known photos of

General Waveren

General "Mule" Wavern - George Custer - Sitting Bull?

Moving General "Mule" Waveren's Cabin

Preparing the transportation.

Moving the cabin from where it has set since the mid 50s.

Wartching and waiting.

W.M. "Mouse" Basket

Hitched and ready to roll.

Spectators came out of the woodwork.

Escort and traffic control.

Arriving at Grigsby Park in Clarita.

Observers from Velma's Kitchen take a break to watch.

Danny Bullard backs the cabin to its final resting place.

The event was documented by Bernie and Aaron Blue

Danny Bullard and Win Rice discuss what a day it was.

"Yea, what a day".

Let's go to the house.

In Coal County